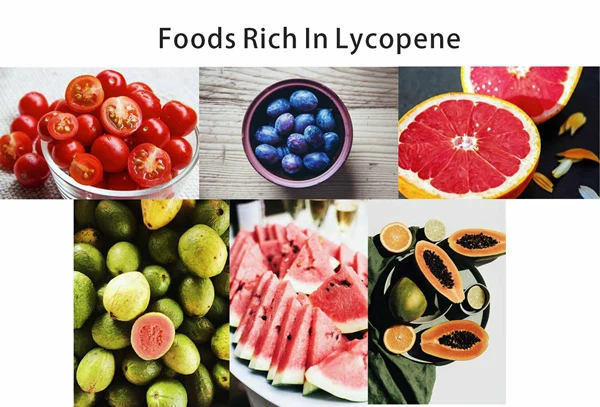

The human body cannot synthesize lycopene and must obtain it from exogenous food. The amount of lycopene in each vegetable and fruit varies, with tomatoes having the highest levels.

Lycopene content in common vegetables and fruits (mg/kg) | |||||

Tomato | Guava | Grapefruit | Watermelon | Papaya | Plum |

50 ~120 | 50~60 | 30~40 | 20~70 | 20~50 | 0.05~0.1 |

After absorption, lycopene is widely distributed in the blood, testis, prostate, breast, ovary and other tissues and organs. Among them, lycopene is more abundant in blood, adrenal gland and testis.

Biosynthesis of Lycopene

During fruit growth and development, the synthesis of lycopene is mainly manifested in two stages:

First, during the discoloration and maturity stage, the color of the fruit changes significantly, and lycopene begins to synthesize and accumulate rapidly until it reaches the highest content. Prior to this, the lycopene content in fruits was very low (such as tomatoes and watermelons).

Second, lycopene starts to be slowly synthesized in the young fruit stage, and is synthesized in large quantities in the mature stage and accumulates rapidly in the fruit (such as red navel orange). This suggests that differences in the developmental stages of different plant genotypes and specific tissues and organs can lead to differences in lycopene synthesis rates.

Distribution and Absorption of Lycopene

The lycopene in the heat-treated tomato juice was more easily absorbed than the untreated one, with a peak serum concentration between 24-48 h and a half-life of 2-3 days. With the increase of food intake, the serum concentration of lycopene increases, but the relationship is not linear, and the cis-form (such as 9-cis, 13-cis) is easier to absorb than the trans-form.

Lycopene is a lipid that must be dissolved in oil for absorption and transport, so the presence of a certain amount of oil is required to increase its bioavailability. Therefore, the addition of lycopene to oleoresin for sustained-release effect can significantly increase the content of oral mucosal cells compared with ingestion of tomato juice. In vivo, it penetrates into chylomicrons through small intestinal mucosal cells, and is then released into the lymph and blood, where it is transported by low-density lipoprotein as a carrier.